Parankimala. A hill overlooking the sea. Years ago, when a group of explorers crossed the seven seas and reached here, it had many kinds of trees, mysterious flowers, plants of the kind never seen, but none that appealed to the visitors. They didn't take the trouble to know what they were or why they were there. Today the hill is acres of rubber plantation that resemble Idukki and Wayanad, from where the adventurous lot had come. Somewhere between the hill and the sea a small town has come up. In appearance, in flavour, in colour it resembles any Kerala town, but drive a few kilometres here or there, you are in a different country. Brazil .

It is highly unlikely the Malayalees took the voyage to the Mecca of Football for their passion for the game. But once here, they embraced the sport, and showered it the love they never showed to kuttiyum kolum (Gully danda).

When the football world cup came here, I had no doubts where I would set up base. Kutty Tea & Toddy came up in one corner of the town, with a clear view of the sea and the bikini. You might wonder what kind of shop mixes tea and toddy, but that is how I am. My day here involves loitering, drinking, eating, watching football and regaling my customers with stories of my adventures, of which I have a long list.

I was busy experimenting with my drinks when a group of youngsters entered my shop. I sized them up. Indians. Wealthy. Fatigued. Homesick. Vulnerable.

"Murugaa 3 shikanji, 2 sambharam and 3 lime water for the beautiful ladies. Table No 5. Welcome to Kutty Tea & Toddy friends."

"How did you know what we wanted?"

"He is Jasoos Narayanan Kutty. He knows all," shouted Georgio, two tables away.

Georgio is a regular here, comes to read newspapers, talk football and listen to my heroics. His real name is quite long, I have jotted it down somewhere, it could be on the calendar, on a newspaper I read months ago, on a restaurant bill...

"Oh, Kutty. You must be from Kerala. How did you land here," one of the guests asked.

"It's a long story. How I, after opening my tea shop in Everest, Moon and Mars, landed in Parankimala."

"A story worth listening to," Georgio gave his approval. The bait was set, but will the prey fall for it?

"Mallu tea shop in Everest and moon, the old joke," one of the visitors said.

"No, no. Kutty can do anything. You just don't know him," Georgio plodded on, "Kutty, tell your story."

"We anyway don't have much to do," said one, "How did you come here?"

"Like I said, it is a long story. It happened long before the Goddess of Small Things won the Booker, Maradona won the World Cup, arrack was banned in Kerala and before I did a Marquez in Malayalam... Speaking of my novel in Malayalam, that is also quite a story. Very interesting and exciting. Should I tell that story first?"

"No. Tell us how you came here."

"OK. As you wish. See children, football in this part of the world is a bit like cricket in Mumbai. It is the lifeline of Brazil . Every town, every village has its own football stories to tell. Every Brazilian identifies with a football team. And they are passionate about their teams. This much you know. What you don't know is the extremes a team will go to to ensure they have an advantage over their rivals. Add to this the rivalry with Argentina and the scouts from Europe . Each of them trying to spot talent. This is where I came into play."

"I thought you were a spy."

"Yes I am. But a CIA friend of mine asked a favour for his friend who was working for a European club. I was asked to search the alleys and beaches of Brazil for the player of the future, the chosen one. Even a headstart of two years would help them buy talent cheap. 'Bypass the system', he said, 'We do not want to wait till he plays the local league'."

"Some kind of inside info."

"Exactly. I infiltrated a community in Rio de Janeiro first. Mingled with them, went to football matches with them, and finally I joined the local team of what we call in India the galli players."

"You play football also?"

"Central defender. Not many appreciate us defenders. But we are the backbone of any successful team. The unsung heroes. The world worships the strikers but how many know about Puyol, Baresi, Maldini."

"Only the connoisseurs."

"Actually, I have won several tournaments in India. As a central defender, I even scored a few goals. One of them I remember vividly. It so happened I took the ball out of our box, and kept running, running and running, dodging one opponent after another. All of a sudden I found myself again in the penalty box. Then I heard someone shout, 'shoot ch****e, shoot.' I didn't think twice, kicked the ball hard. Goooooooaaaaaaaaaaallllllllllllllll."

"You made up the story, didn't you?"

"You don't believe me. See this is how I did it."

I took a football from the shelf, took aim at an imaginary goalpost, shot the ball to the top left corner of the post. Seconds later we heard the egg seller down the road scream, giving us an exact location of where it landed. It happens. You need a large heart to understand football, and Brazilians have it. But this particular egg seller walked down, seeking damages. My worst fears were confirmed. He was a 24-carat Malayalee. People like him sully Brazil's name. I had to shell out a few reals to get him off my back.

"That must have been quite a goal."

"Kutty omitted one bit," said Murugan bringing our guests crispy vadas soaked in sambhar, "It was a self goal."

Let me tell you one thing, man to man, heart to heart. Never, ever help a bachpan ka friend. Even if you want to, never employ him in your business. These langotiya yaars will out you every chance they get just to prove how close we are.

"Kutty and I are childhood friends. We went to the same school, sat on the same bench, ate from the same plate, when there was no food in his house, I used to get him pazhankanji. He still remembers those years. He brought me here, to Brazil, gave me work. So what if it's just a waiter's job, at least he did that much."

See this is what I said. Never, ever employ a bachpan ka friend, he will do this to you.

"The referee called it a self goal. But to this day, I believe there was some fixing."

"Kutty, I believe you," said one of the women, and gifted me a lovely smile.

"If not for you, what would this world be! What is your name?"

"Let us say my name is Dhanno."

"Such a nice name, Basanti would have been better."

"Kutty, the story please."

"Yeah the story. Which one?"

"Your clandestine mission in Brazil to scout soccer talent."

"The team I joined, I again became the central defender. We played in several cities, villages, on the streets, in the fields, on the beaches, on every vacant bit of land we could find. But soon I found myself in trouble."

"What happened?"

"See, I take my job very seriously. In this case the defender's job. I perfected the art of adangi maarna there. No striker worth his salt could get past me. Soon maar adangi became a common phrase in our part of Brazil, and I became the focus of attention. Bigger local clubs started approaching me to sign me up."

"Did you sign for any club," asked Dhanno.

"No. I was here on a different mission. I couldn't have. Then one day I met my match. A striker who could break the chakravyuh I built. A young boy with magnetic boots. Unbelievable ball control. As if the ball was tied to his boots with a string. He decided if he needed to loosen the string or tighten it. He dribbled like a ballet dancer, swerving, ducking, leaping... what a beauty. You could compose music to match his moves on the pitch. He broke down our defences at will, scored two goals."

"You lost the match."

"We scored two of ours. But it became a prestige issue for me. If he breaks down the fort I built, then he will have to become Abhimanyu, I decided. We asked two of players to mark him. If he gets the ball in the box, create a melee out there, a free for all. It worked fine till the 90th minute. He came like a raging bull, skipping every adangi on the way."

"Then what happened."

"Well, there was no way I was going to allow him a goal. I did what was required of me."

"You brought him down."

"You kicked him"

"You broke his leg."

"Something similar. I hit him where it hurts most."

"What do you mean?"

"The oldest trick in gali football. I caught him by his balls."

"No, you didn't."

I took Dhanno's sambharam, poured a little vodka into it, drank it in one go and started telling them the story of my novel in Malayalam. It is better than Marquez, I guarantee.

Sastry, the first non-founder to get on the Infosys board, plays down his generosity saying that he was only returning a favour.

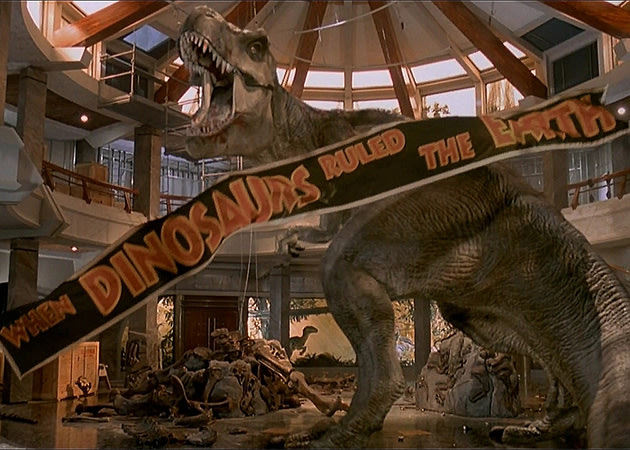

Universal Pictures

Universal Pictures Universal Pictures

Universal Pictures Jurassic Park

Jurassic Park Universal Pictures

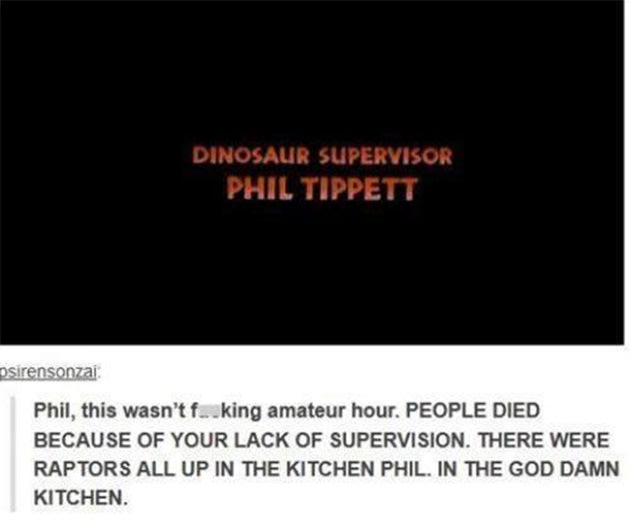

Universal Pictures via Tumblr

via Tumblr