Monday, June 22, 2020

Prime’s free movies: Becoming Jane

Sunday, June 14, 2020

Where’s the peak ?

I honestly cannot believe we are now 6 months into this year. This pandemic filled nightmare year. How could we have got this so wrong ? 2020 was going to be the fancy year, the fun and happening year. The culmination of two decades into the millennium, the yeas in which millennials turn adults. And , if you subscribed to the political propaganda, and had read the books of Abdul Kalam, this was the year India was going to makes its mark (Remember the book, India 2020 ?)on the world.

Well India has left

and will leave its mark on the world. The world’s largest lockdown has turned

out to be hogwash, and India has accelerated itself into the top 5 of the world’s

COVID affected countries. Long predicted by the world’s non-Indian infectious disease

experts, this statement was ‘fake-news’ed by India’s politicians early on. Even

now, the Govt denies India has community spread, and is getting ready to

organize political rallies for the upcoming state elections.

And here is the bare

truth : we are yet to peak.

It does not inspire

confidence when scientific consensus is thrown out in favour of political propaganda.

To be fair, India is not the only country to do so, almost every country has fudged

their numbers, if rumour is to be believed, to look better than others. But while

some others have genuinely put in the hard work and effort to fight this

invisible enemy, ours is a case of being attacked on multiple fronts.

The plights of India’s

poor migrant labours was the first of these. This was followed by reported

intrusion at the border with China. And now , the country is hearing about the

border being redrawn with our northern ally Nepal. PM Modi and his cabinet has long denied the reported

slow down in our economy, but now the pandemic has brought it to stop. There is

now a half planned, and half-hearted attempt to restart manufacturing in this

troubled economy, and to ‘turn the virus into an opportunity’. It is balderdash

that the nation can do in a few months what it could not do in more than 70

years. But the biggest gobbledygook of all was the stimulus package announced

by the govt, which was mostly repackaging of previously announced plans, with

the govt delegating responsibility of the stimulus to the nation’s

already trouble banks. It did not help that a section of the media sided with the

govt’s lies to keep the people in the

blind.

Day to day life has now

become increasingly dangerous in India. The govt no longer cares (if it ever

did) about its people, and is focussed on upcoming elections, and making the

people work for the govt, instead of the other way around.

Ask not, they say,

what the nation can do for the people, but what the people can further do for

the nation.

Saturday, June 6, 2020

Thursday, May 28, 2020

Everyone expects India's economy to contract. Everyone.

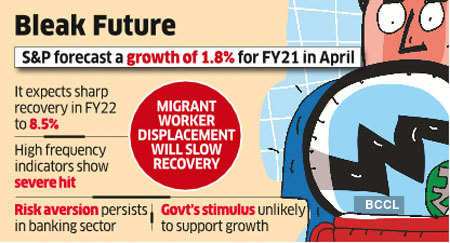

S&P Global

Ratings on Thursday said the Indian economy will shrink by 5 per cent in

the current fiscal as it joined a chorus of international agencies that are

forecasting a contraction in growth rate due to coronavirus lockdown

halting economic activity.

Stating that COVID-19 has not yet been contained in

India, the rating agency in a statement said the government stimulus package is

low relative to countries with similar economic impacts from the pandemic.

"The COVID-19 outbreak in India and two months

of lockdown -- longer in some areas -- have led to a sudden stop in the

economy. That means growth will contract sharply this fiscal year (April 2020

to March 2021)," it said. "Economic activity will face ongoing

disruption over the next year as the country transitions to

a post-COVID-19 world."

Forecasting a 5 per cent contraction in 2020-21

(versus 1.8 per cent growth forecast it

made in April), S&P said growth is expected to pick up to 8.5 per cent in

the following fiscal (up from the previous forecast of 7.5 per cent). The GDP

is projected to expand by 6.5 per cent in FY23 and 6.6 per cent FY24.

Earlier this week, Fitch Ratings and Crisil, too,

projected a 5 per cent contraction for the Indian economy.

While Fitch Ratings had stated that India has had a very stringent lockdown

policy that has lasted a lot longer than initially expected and incoming

economic activity data have been spectacularly weak, Crisil had said the

country's fourth recession since Independence, first since liberalisation, and

perhaps the worst to date, is here.

On Thursday, Fitch Solutions (which is separate

from Fitch Ratings) forecast real GDP to contract by 4.5 per cent in FY2020-21

saying "high unemployment will depress consumer spending, while widespread

economic uncertainties will curb investment in the private sector.

Moody's Investors Service on May 8, forecast a

'zero' growth rate for India in FY21.

In the past 69 years, India has seen a recession

only thrice – as per available data – in fiscal year 1958, 1966 and 1980. A

monsoon shock that hit agriculture, then a sizeable part of the economy, was

the reason on all three occasions.

This time around agriculture is not the reason but

a dent to industrial and economic activity caused by lockdown, which was first

imposed on March 25. The lockdown has been extended thrice till May 31 with

some easing of restrictions.

S&P Global Ratings expects varying degrees of

containment measures and economic resumption across India during this

transition.

"COVID-19 has not yet been contained in India.

New cases have been averaging more than 6,000 a day over the past week as

authorities begin easing stringent lockdown restrictions gradually to prevent

economic costs from blowing out further. We currently assume that the outbreak

peaks by the third quarter," it said.

India has grouped geographical zones into red,

orange, or green categories based on the number of cases. Areas currently

classified as red zones are also economically significant, and the authorities

could extend mobility restrictions.

"We believe economic activity in these places

will take longer to normalize. This will have knock-on impacts on countrywide

supply chains, which will slow the overall recovery," it said.

The rating agency said high-frequency data for

April showed major economic costs for India - purchasing managers index (PMI)

for the services sector was 5.4, on a scale where anything below 50 indicates a

contraction of business activity from the previous month for the sector.

Also, service sectors, which account for high

shares of employment, have been severely affected, thus leading to large-scale

job losses across the country. Workers have been geographically displaced as

migrant workers travelled back home before the lockdown, and this will take

time to unwind as lockdown measures are lifted.

"We expect that employment will remain

depressed over the transition period," it said.

S&P said India has limited room to maneuver on

policy support. The Reserve Bank of India has cut policy rates by 115 basis

points but banks have been unwilling to extend credit. Small and mid-size

enterprises continue to face restricted access to credit markets despite some

policy measures aimed at easing financing for the sector.

"The government's stimulus package, with a

headline amount of 10 per cent of GDP, has about 1.2 per cent of direct

stimulus measures, which is low relative to countries with similar economic

impacts from the pandemic. The remaining 8.8 per cent of the package includes

liquidity support measures and credit guarantees that will not directly support

growth," it said.

The rating agency said the big hit to growth will

mean a large, permanent economic loss and a deterioration in balance sheets throughout

the economy.

"The risks around the path of recovery will

depend on three key factors. First, the speed with which the COVID-19 outbreak

comes under control. Faster flattening of the curve -- in other words, reducing

the number of new cases -- will potentially allow faster normalization of

activity. Second, a labour market recovery will be key to getting the economy

running again. Finally, the ability of all sectors of the economy to restore

their balance sheets following the adverse shock will be important. The longer

the duration of the shock, the longer recovery," it added.

Acknowledging a high degree of uncertainty about

the rate of spread and peak of the coronavirus outbreak, it said some

government authorities estimate the pandemic will peak around mid-year, and

that has been used as an assumption in assessing the economic and credit

implications.

Wednesday, April 22, 2020

The Kerala model

Boosted to begin with by economists and demographers, Kerala

soon came in for praise from sociologists and political scientists. The former

argued that caste and class distinctions had radically diminished in Kerala

over the course of the 20th century; the latter showed that, when it came to

implementing the provisions of the 73rd and 74th Amendments to the

Constitution, Kerala was ahead of other states. More power had been devolved to

municipalities and panchayats than elsewhere in India.

Success, as John F. Kennedy famously remarked, has many fathers

(while failure is an orphan). When these achievements of the state of Kerala

became widely known, many groups rushed to claim their share of the credit. The

communists, who had been in power for long stretches, said it was their

economic radicalism that did it. Followers of Sri Narayana Guru (1855-1928)

said it was the egalitarianism promoted by that great social reformer which led

to much of what followed. Those still loyal to the royal houses of Travancore

and Cochin observed that when it came to education, and especially girls'

education, their Rulers were more progressive than Maharajas and Nawabs

elsewhere. The Christian community of Kerala also chipped in, noting that some

of the best schools, colleges, and hospitals were run by the Church. It was

left to that fine Australian historian of Kerala and India, Robin Jeffrey, to

critically analyse all these claims, and demonstrate in what order and what

magnitude they contributed. His book Politics,

Women and Wellbeing remains the definitive work on the

subject.

Such were the elements of the 'Kerala Model'. What did the

'Gujarat Model' that Narendra Modi began speaking of, c. 2007, comprise? Mr

Modi did not himself ever define it very precisely. But there is little doubt

that the coinage itself was inspired and provoked by what had preceded it. The

Gujarat Model would, Mr Modi was suggesting, be different from, and better

than, the Kerala Model. Among the noticeable weaknesses of the latter was that

it did not really encourage private enterprise. Marxist ideology and trade

union politics both inhibited this. On the other hand, the Vibrant Gujarat

Summits organized once every two years when Mr Modi was Chief Minister were

intended precisely to attract private investment.

This openness to private capital was, for Mr Modi's supporters,

undoubtedly the most attractive feature of what he was marketing as the

'Gujarat Model'. It was this that brought to him the support of big business,

and of small business as well, when he launched his campaign for Prime

Minister. Young professionals, disgusted by the cronyism and corruption of the

UPA regime, flocked to his support, seeing him as a modernizing Messiah who

would make India an economic powerhouse.

With the support of these groups, and many others, Narendra Modi

was elected Prime Minister in May 2014.

There were other aspects of the Gujarat Model that Narendra Modi

did not speak about, but which those who knew the state rather better than the

Titans of Indian industry were perfectly aware of. These included the

relegation of minorities (and particularly Muslims) to second-class status; the

centralization of power in the Chief Minister and the creation of a cult of

personality around him; attacks on the independence and autonomy of

universities; curbs on the freedom of the press; and, not least, a vengeful

attitude towards critics and political rivals.

These darker sides of the Gujarat Model were all played down in

Mr Modi's Prime Ministerial campaign. But in the six years since he has been in

power at the Centre, they have become starkly visible. The communalization of

politics and of popular discourse, the capturing of public institutions, the

intimidation of the press, the use of the police and investigating agencies to

harass opponents, and, perhaps above all, the deification of the Great Leader

by the party, the Cabinet, the Government, and the Godi Media -

these have characterized the Prime Ministerial tenure of Narendra Modi.

Meanwhile, the most widely advertised positive feature of the Gujarat Model

before 2014 has proved to be a dud. Far from being a free-market reformer,

Narendra Modi has demonstrated that he is an absolute statist in economic

matters. As an investment banker who once enthusiastically supported him

recently told me in disgust: "Narendra Modi is our most left-wing Prime

Minister ever - he is even more left-wing than Jawaharlal Nehru".

Which brings me back to the Kerala Model, which the Gujarat

Model sought to replace or supplant. Talked about a great deal in the 1980s and

1990s, in recent years, the term was not much heard in policy discourse any

more. It had fallen into disuse, presumably consigned to the dustbin of

history. The onset of COVID-19 has now thankfully rescued it, and indeed

brought it back to centre-stage. For in how it has confronted, tackled, and

tamed the COVID crisis, Kerala has once again showed itself to be a model for

India - and perhaps the world.

There has been some excellent reporting on how Kerala flattened the curve. It seems clear

that there is a deeper historical legacy behind the success of this state.

Because the people of Kerala are better educated, they have followed the

practices in their daily life least likely to allow community transmission.

Because they have such excellent health care, if people do test positive, they

can be treated promptly and adequately. Because caste and gender distinctions

are less extreme than elsewhere in India, access to health care and medical

information is less skewed. Because decentralization of power is embedded in

systems of governance, panchayat heads do not have to wait for a signal from a

Big Boss before deciding to act. There are two other features of Kerala's

political culture that have helped them in the present context; its top leaders

are generally more grounded and less imperious than elsewhere, and

bipartisanship comes more easily to the state's politicians.

The state of Kerala is by no means perfect. While there have

been no serious communal riots for many decades, in everyday life there is

still some amount of reserve in relations between Hindus, Christians and

Muslims. Casteism and patriarchy have been weakened, but by no means

eliminated. The intelligentsia still remain unreasonably suspicious of private

enterprise, which will hurt the state greatly in the post-COVID era, after

remittances from the Gulf have dried up.

For all their flaws, the state and people of Kerala have many

things to teach us, who live in the rest of India. We forgot about their

virtues in the past decade, but now these virtues are once more being

discussed, to both inspire and chastise us. The success of the state in the

past and in the present have rested on science, transparency, decentralization,

and social equality. These are, as it were, the four pillars of the Kerala

Model. On the other hand, the four pillars of the Gujarat Model are

superstition, secrecy, centralization, and communal bigotry. Give us the first

over the second, any day.