The well-publicized debate at the Creation Museum was not about two minds sparring.

original

Enlarge / Adams' Synchronological Chart of Universal History.

In 1878, the American scholar and minister Sebastian Adams put the final touches on the third edition of his grandest project: a massive Synchronological Chart that covers nothing less than the entire history of the world in parallel, with the deeds of kings and kingdoms running along together in rows over 25 horizontal feet of paper. When the chart reaches 1500 BCE, its level of detail becomes impressive; at 400 CE it becomes eyebrow-raising; at 1300 CE it enters the realm of the wondrous. No wonder, then, that in their 2013 bookCartographies of Time: A History of the Timeline, authors Daniel Rosenberg and Anthony Grafton call Adams' chart "nineteenth-century America's surpassing achievement in complexity and synthetic power... a great work of outsider thinking."

The chart is also the last thing that visitors to Kentucky's Creation Museum see before stepping into the gift shop, where full-sized replicas can be purchased for $40.

Further Reading

Gap theory, "old Earth creationism," and more.

That's because, in the world described by the museum, Adams' chart is more than a historical curio; it remains an accurate timeline of world history. Time is said to have begun in 4004 BCE with the creation of Adam, who went on to live for 930 more years. In 2348 BCE, the Earth was then reshaped by a worldwide flood, which created the Grand Canyon and most of the fossil record even as Noah rode out the deluge in an 81,000 ton wooden ark. Pagan practices at the eight-story high Tower of Babel eventually led God to cause a "confusion of tongues" in 2247 BCE, which is why we speak so many different languages today.

Adams notes on the second panel of the chart that "all the history of man, before the flood, extant, or known to us, is found in the first six chapters of Genesis."

Ken Ham agrees. Ham, CEO of Answers in Genesis (AIG), has become perhaps the foremost living young Earth creationist in the world. He has authored more books and articles than seems humanly possible and has built AIG into a creationist powerhouse. He also made national headlines when the slickly modern Creation Museum opened in 2007.

Enlarge / Ken Ham meets the press before the debate.

He has also been looking for the opportunity to debate a prominent supporter of evolution.

And so it was that, as a severe snow and sleet emergency settled over the Cincinnati region, 900 people climbed into cars and wound their way out toward the airport to enter the gates of the Creation Museum. They did not come for the petting zoo, the zip line, or the seasonal camel rides, nor to see the animatronic Noah chortle to himself about just how easy it had really been to get dinosaurs inside his Ark. They did not come to see The Men in White, a 22-minute movie that plays in the museum's halls in which a young woman named Wendy sees that what she's been taught about evolution "doesn't make sense" and is then visited by two angels who help her understand the truth of six-day special creation. They did not come to see the exhibits explaining how all animals had, before the Fall of humanity into sin, been vegetarians.

Further Reading

Ars takes in the sights and sounds of Ken Ham's magnum opus.

They came to see Ken Ham debate TV presenter Bill Nye the Science Guy—an old-school creation v. evolution throwdown for the Powerpoint age. Even before it began, the debate had been good for both men. Traffic to AIG's website soared by 80 percent, Nye appeared on CNN, tickets sold out in two minutes, and post-debate interviews were lined up with Piers Morgan Live and MSNBC.

While plenty of Ham supporters filled the parking lot, so did people in bow ties and "Bill Nye is my Homeboy" T-shirts. They all followed the stamped dinosaur tracks to the museum's entrance, where a pack of AIG staffers wearing custom debate T-shirts stood ready to usher them into "Discovery Hall."

Security at the Creation Museum is always tight; the museum's security force is made up of sworn (but privately funded) Kentucky peace officers who carry guns, wear flat-brimmed state trooper-style hats, and operate their own K-9 unit. For the debate, Nye and Ham had agreed to more stringent measures. Visitors passed through metal detectors complete with secondary wand screenings, packages were prohibited in the debate hall itself, and the outer gates were closed 15 minutes before the debate began.

Enlarge / The scene inside the auditorium.

Inside the hall, packed with bodies and the blaze of high-wattage lights, the temperature soared. The empty stage looked—as everything at the museum does—professionally designed, with four huge video screens, custom debate banners, and a pair of lecterns sporting Mac laptops. 20 different video crews had set up cameras in the hall, and 70 media organizations had registered to attend. More than 10,000 churches were hosting local debate parties. As AIG technical staffers made final preparations, one checked the YouTube-hosted livestream—242,000 people had already tuned in before start time.

An AIG official took the stage eight minutes before start time. "We know there are people who disagree with each other in this room," he said. "No cheering or—please—any disruptive behavior."

At 6:59pm, the music stopped and the hall fell silent but for the suddenly prominent thrumming of the air conditioning. For half a minute, the anticipation was electric, all eyes fixed on the stage, and then the countdown clock ticked over to 7:00pm and the proceedings snapped to life. Nye, wearing his traditional bow tie, took the stage from the left; Ham appeared from the right. The two shook hands in the center to sustained applause, and CNN's Tom Foreman took up his moderating duties.

Enlarge / Ken Ham makes his opening remarks as Bill Nye looks on.

Ham had won the coin toss backstage and so stepped to his lectern to deliver brief opening remarks. "Creation is the only viable model of historical science confirmed by observational science in today's modern scientific era," he declared, blasting modern textbooks for "imposing the religion of atheism" on students.

"We're teaching people to think critically!" he said. "It's the creationists who should be teaching the kids out there."

And we were off.

Two kinds of science

Digging in the fossil fields of Colorado or North Dakota, scientists regularly uncover the bones of ancient creatures. No one doubts the existence of the bones themselves; they lie on the ground for anyone to observe or weigh or photograph. But in which animal did the bones originate? How long ago did that animal live? What did it look like? One of Ham's favorite lines is that the past "doesn't come with tags"—so the prehistory of a stegosaurus thigh bone has to be interpreted by scientists, who use their positions in the present to reconstruct the past.

For mainstream scientists, this is simply an obvious statement of our existential position. Until a real-life Dr. Emmett "Doc" Brown finds a way to power a Delorean with a 1.21 gigawatt flux capacitor in order to shoot someone back through time to observe the flaring-forth of the Universe, the formation of the Earth, or the origins of life, or the prehistoric past can't be known except by interpretation. Indeed, this isn't true only of prehistory; as Nye tried to emphasize, forensic scientists routinely use what they know of nature's laws to reconstruct past events like murders.

Enlarge / Ken Ham's starting point for doing "historical science."

For Ham, though, science is broken into two categories, "observational" and "historical," and only observational science is trustworthy. In the initial 30 minute presentation of his position, Ham hammered the point home.

"You don't observe the past directly," he said. "You weren't there."

Ham spoke with the polish of a man who has covered this ground a hundred times before, has heard every objection, and has a smooth answer ready for each one.

When Bill Nye talks about evolution, Ham said, that's "Bill Nye the Historical Science Guy" speaking—with "historical" being a pejorative term.

In Ham's world, only changes that we can observe directly are the proper domain of science. Thus, when confronted with the issue of speciation, Ham readily admits that contemporary lab experiments on fast-breeding creatures like mosquitoes can produce new species. But he says that's simply "micro-evolution" below the family level. He doesn't believe that scientists can observe "macro-evolution," such as the alteration of a lobe-finned fish into a tiger over millions of years.

Because they can't see historical events unfold, scientists must rely on reconstructions of the past. Those might be accurate, but they simply rely on too many "assumptions" for Ham to trust them. When confronted during the debate with evidence from ancient trees which have more rings than there are years on the Adams Sychronological Chart, Ham simply shrugged.

"We didn't see those layers laid down," he said.

To him, the calculus of "one ring, one year" is merely an assumption when it comes to the past—an assumption possibly altered by cataclysmic events such as Noah's flood.

In other words, "historical science" is dubious; we should defer instead to the "observational" account of someone who witnessed all past events: God, said to have left humanity an eyewitness account of the world's creation in the book of Genesis. All historical reconstructions should thus comport with this more accurate observational account.

Mainstream scientists don't recognize this divide between observational and historical ways of knowing (much as they reject Ham's distinction between "micro" and "macro" evolution). Dinosaur bones may not come with tags, but neither does observed contemporary reality—think of a doctor presented with a set of patient symptoms, who then has to interpret what she sees in order to arrive at a diagnosis.

Given that the distinction between two kinds of science provides Ham's key reason for accepting the "eyewitness account" of Genesis as a starting point, it was unsurprising to see Nye take generous whacks at the idea. You can't observe the past? "That's what we do in astronomy," said Nye in his opening presentation. Since light takes time to get here, "All we can do in astronomy is look at the past. By the way, you're looking at the past right now."

Those in the present can study the past with confidence, Nye said, because natural laws are generally constant and can be used to extrapolate into the past.

"This idea that you can separate the natural laws of the past from the natural laws you have now is at the heart of our disagreement," Nye said. "For lack of a better word, it's magical. I've appreciated magic since I was a kid, but it's not what we want in mainstream science."

How do scientists know that these natural laws are correctly understood in all their complexity and interplay? What operates as a check on their reconstructions? That's where the predictive power of evolutionary models becomes crucial, Nye said. Those models of the past should generate predictions which can then be verified—or disproved—through observations in the present.

An artist's conception of Tiktaalik roseae.

For instance, evolutionary models suggest that land-based tetrapods can all be traced back to primitive, fish-like creatures that first made their way out of the water and onto solid ground—creatures that aren't quite lungfish and yet aren't quite amphibians. For years, there was a big gap in the fossil record around this expected transition. Then, in 2004, a research team found a number of these "fishapods" in the Canadian Arctic.

"Tiktaalik looks like a cross between the primitive fish it lived amongst and the first four-legged animals," wrote the research team as they introduced their discovery to the world.

"What we want in science—science as practiced on the outside—is the ability to predict," said Nye, pointing to the examples of Tiktaalik in biological evolution and the results of the Cosmic Background Explorer mission in cosmology. Mainstream scientific predictions, even those focused on the past, can in fact be tested against reality. So far, however, "Mr. Ham and his worldview does not have this capability," Nye said. "It cannot make predictions and show results."

At the infamous Scopes trial of 1925, the state of Tennessee prosecuted a young science teacher for teaching evolution in public schools. The trial became a sensation after two of the most famous lawyers in the country showed up to the courthouse in Dayton, Tennessee and argued opposite sides of the case.

On the seventh day of the trial, a rumor went round the courthouse that the courtroom floor was failing and might collapse beneath the weight of so many spectators. The judge then moved the entire proceedings outside onto the lawn.

Clarence Darrow, the lawyer defending Scopes, immediately saw a problem with this new arrangement: a sign hanging on the outer courthouse wall.

Clarence Darrow, the lawyer defending Scopes, immediately saw a problem with this new arrangement: a sign hanging on the outer courthouse wall.

"Right before [the jury] was a great sign flaunting letters two feet high, where every one could see the magic words: 'READ YOUR BIBLE DAILY,'" he later recounted.

Darrow objected to the sign and asked the judge to remove it.

"If your honor please, why should it be removed?" asked a lawyer for the state, according to the trial transcript. "It is their defense and stated before the court that they do not deny the Bible, that they expect to introduce proof to make it harmonize [with evolution]. Why should we remove the sign cautioning the people to read the Word of God just to satisfy the others in the case?"

But Darrow was firm. If the sign wouldn't go, "We might agree to get up a sign of equal size on the other side and in the same position reading, Hunter's Biology or Read your evolution," he said. "This sign is not here for no purpose, and it can have no effect but to influence this case."

The judge made his own position clear, saying, "If the Bible is involved, I believe in it and am always on its side."

Darrow found himself working against all three branches of government: the legislature (which had passed the anti-evolution law), the executive (which was prosecuting the case), and the judiciary (which had just decreed its allegiance to the Bible in all cases).

In the end, the sign was removed, but Scopes was eventually found guilty and fined $100 (the decision was reversed on a technicality during appeal).

90 years on, the cultural landscape has changed dramatically. The Supreme Court has outlawed the teaching of creationism in public schools as an unconstitutional endorsement of religion by the state. Courthouses no longer sport signs telling people to "READ YOUR BIBLE DAILY." State laws don't ban the teaching of evolution (though there are regular attemptsto endorse intelligent design or "teach the controversy" approaches to the subject).

Whatever doubts about evolution that remained in the mainstream scientific community in 1925 have largely been expunged by a flood of new information, especially from genetics. In 1950, the Catholic church even explicitly allowedresearch on "the doctrine of evolution, in as far as it inquires into the origin of the human body as coming from pre-existent and living matter" (the soul, however, was reserved for God alone). Among mainline Protestants, only 15 percent or so deny evolution.

Six-day, young-Earth, special creationism might therefore be expected to occupy a niche position today—but it does not. In 2012, a Gallup poll found that 46 percent of all Americans "believe in the creationist view that God created humans in their present form at one time within the last 10,000 years." In December 2013, a Pew poll found that 33 percent of Americans reject all forms of evolution.

Enlarge / The Creation Museum in Petersburg, Kentucky.

Ham's AIG has been able to capitalize on this wide support for creationism. According to Eugenie Scott, head of the National Center for Science Education, AIG is now the largest young-Earth creationist group in the United States. Ken Ham started AIG in 1993 after moving on from another young-Earth organization and moving to Kentucky; by 2007, he had dreamed up and then built the $27 million Creation Museum. Two million people have visited since.

According to the most recent data submitted to the Internal Revenue Service, AIG now pulls in $22 million a year and employs 351 people—including Ham's brother, three of Ham's daughters, one son, a son-in-law, and a daughter-in-law. Most of the cash appears to be spent on operations; Ham is the only employee to make more than $100,000 (he gets a $134,000 salary). Even with a $30 ticket price—more than it costs to visit the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York—the Creation Museum cost almost $8 million a year to run in fiscal year 2012 but generated only $4.9 million from admission fees.

Enlarge / Like every other museum and zoo exhibit, the exit goes through the gift shop.

More lucrative is AIG's bookstore and shipping operation, which made $2 million in profit by selling books and DVDs like The Homosexual War, The Lie, and The War on Christmas. AIG's quarterly magazine, Answers, shipped 300,000 copies around the world in 2012, while its website served 31 million pageviews.

Despite the movement's success, however, many creationists feel "looked down upon" by social, media, and scientific elites. Creationism might have plenty of adherents, but those adherents would also like respect.

Ham used the debate as a way to argue that young Earth creationists deserved that respect. His presentation was peppered with video clips from scientists like Raymond Damadian, inventor of the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technique. Ham's point was that, whatever views of origins someone holds, they are not necessarily Luddites—and they can still practice excellent "observational science."

The world of 1925 might never return, but the debate gave Ham a broad platform to make his case that the mainstream scientific establishment has made too many creationists scared to speak up; they need scientific "freedom," he said.

“My Kentucky friends”

"Scientists should not debate creationists. Period," wrote Dan Arel in a piece published on the Richard Dawkins Foundation website last month. "Creationism is a worthless and uneducated position to hold in our modern society and Nye is about to treat it as an equal, debatable 'controversy'."

Nye's appearance with Ham has broken a widespread taboo in science against engaging in such debates. Why the refusal to debate? In her 2004 article "Debates: The Drive-By Shootings of Critical Thinking," published by the National Center for Science Education, professor Karen Bartelt argued that the complete evidence for evolution is simply not possible to summarize in a two-hour debate, and that the audience is often not equipped to evaluate competing claims in real-time.

Besides, mainstream scientists see the evolution issue as settled. "Scientists do not debate whether the Earth goes around the sun, whether the Earth is spherical or flat, or whether humans have 46 chromosomes; instead, they evaluate evidence," she wrote. "It is wrong to imply to general audiences that [debates are] the way science is done."

Scientist and author Richard Dawkins subscribes to the same view. He once told the story of how he was invited to do a similar debate with a leading creationist in the US during the 1980s. He called fellow scientist and writer Stephen Jay Gould for advice.

[Gould] was friendly and decisive: "Don't do it." The point is not, he said, whether or not you would "win" the debate. Winning is not what the creationists realistically aspire to. For them, it is sufficient that the debate happens at all. They need the publicity. We don't. To the gullible public which is their natural constituency, it is enough that their man is seen sharing a platform with a real scientist.

For all these reasons, Nye came in for significant criticism from the scientific community. Though well-spoken and a gifted communicator, Nye's own background is as a mechanical engineer, not a biologist. He had also agreed to do the debate at the Creation Museum itself, as far from a "neutral" site as one could imagine. Would he manage any more than publicizing Ken Ham's face, ideas, and exhibits?

But 150 years of post-Darwin science has not convinced huge swaths of the American public of evolution's truth. The debate promised Nye a huge platform for speaking directly to that public about science education—over 500,000 people watched the live YouTube-hosted stream alone—and he took it, speaking directly to the audience in a way Ham never attempted.

"My Kentucky friends, I want you to consider this," Nye said earnestly, sometimes addressing those in the room but more often speaking to the cameras. "We're here in Kentucky upon layer upon layer upon layer of limestone."

Nye told the audience how he had stopped by the side of the road and picked up a piece of limestone with a small fossil in it—and then he held up the stone for everyone to see.

"We are standing on millions of layers of ancient life," he said, arguing that ancient animals could not have lived their lives and formed limestone's many layers in just a few thousand years, given what we know about fossilization and sedimentation.

He then implored voters in Texas, Oklahoma, and other states to support mainstream scientific education, saying that they didn't want a generation of kids who didn't understand natural law.

Nye spoke clearly, with bits of folksy humor thrown in, and made a compelling case for his side. On the science, his most devastating pieces of evidence simply went unchallenged; Ham just argued that they relied on the "assumptions" of "historical science."

Nye misfired a few times when moving away from the science. For instance, he repeatedly blasted Ham's reliance on biblical "verses translated into American English over 30 centuries," comparing the process to a game of telephone in which words get mangled. Since we still have the many early texts used to generate all those translations, and since scholars can still read them, and since all serious English translations are translated directly from them, the point lacked rhetorical force.

In the debate's aftermath, many of Nye's critics agreed that he had acquitted himself well. But did the strength of the performance even matter? As though confirming the fears of Dawkins and others, even some creationists admitted that Nye won the debate—but they argued that Ham "won by losing" in raising "huge awareness about Biblical Creationism on a mammoth scale. Over 500,000 computers logged in? Not bad! He planted seeds of hope that the Bible is true and seeds of doubt that evolution is our only model."

The origin of species

Noah's Ark resting on Mount Ararat.

Six feet into the Adams Synchronological Chart sits a beautiful color illustration of Noah's Ark resting on Mount Ararat, a rainbow spanning the sky above it. Adams follows the biblical account in claiming that the Ark carried eight individuals: Noah, his wife, his three sons, and their wives. In 2247 BCE, after the waters drained away and this small family left their boat for the wider world, they had to repopulate it. Adams accepts an old Armenian tradition that links each ethnic group to one of Noah's grandsons—Shem's son Aram produced the Syrians, for instance, while Japheth's son Javan gave us Spaniards.

Accepting this history creates problems, however, even on its own terms. In the 4,000 years said to have elapsed since the Flood, humans have populated the whole Earth but have remained the same species, with the ability to interbreed with any other human. How then did the pairs of animal "kinds" on the Ark produce the millions of species we see today in such a narrow window of time?

That question became Nye's single most effective attack of the night.

Enlarge / Given the number of species in the world, we should have been discovering about 11 per day since the flood, if the chronology presented by Ken Ham were correct.

Nye offered a simple equation that accepted Ham's logic: in the 4,000 years since the Flood, 7,000 "kinds" of animals have led to at least 16,000,000 species today. (Ham believes that God only stocked the Ark with "kinds" of creatures, which are roughly equivalent to "families," and these later diversified. One pair of dogs, for instance, became all dogs we see today.) This would mean that, on average, 11 new species have emerged on Earth every single day since the Flood—which is plainly not happening. (In reality, the situation is even worse, since Ham believes only 1,000 "kinds" were on the Ark and Nye argues there may actually be as many as 50,000,000 species on the Earth today.)

This is literally incredible, even to Ham. A hundred yards away from the sweltering debate hall, in the middle of the winding path through the Creation Museum's exhibits, just around the corner from the animatronic Noah, an exhibit shows the way "Life Recovers" after the Flood. It depicts the speciation of horses, but some tiny text at the bottom explains that the math doesn't really add up. "Present changes are too small and too slow to explain these differences," it says, "suggesting God provided organisms with special tools to change rapidly."

Enlarge / "Present changes are too small and too slow to explain these differences, suggesting God provided organisms with special tools to change rapidly."

No evidence is offered for this position, which is textbook "God of the gaps" thinking in which God's miraculous power can be used to plug up the holes in an argument.

The speciation question revealed just how far Nye and Ham were talking past one another. Nye wanted evidence; Ham had his eyewitness account, which no evidence could alter. Near the end of the debate, one audience member had a question for both of them: what might change your mind?

Nye said that he could be convinced by fossil record evidence, by some compelling explanation of how we can see the light from stars that are millions of light years away, by an explanation of how radioactive decay rates might have differed in the past.

But not Ham. "No one's ever going to convince me that the word of God isn't true," he said.

That sets Ham apart from people like Sebastian Adams, who penned a short note on method at the beginning of his Synchronological Chart. While the best records he had indicated that Adam was the first human, Adams was open to new evidence.

"If any critic has historic information of any person and people that antedate those given, having all these specified dates," he wrote, "it will be most thankfully received and properly considered in subsequent editions of this work."

“Just nonsense"

Enlarge / A church a couple of miles up the road from the Creation Museum has a different take on Genesis.

A mile up the road from the Creation Museum sits the small Bullittsville Christian Church. On the day of the debate, its sign read, "The book of Genesis is about who, not how."

As with "historical science," texts in the Bible don't come with tags; they always require interpretation. The early church father Origen famously trashed those who believed a literal account of the Genesis creation story, writing in his De Principiis:

For who that has understanding will suppose that the first, and second, and third day, and the evening and the morning, existed without a sun, and moon, and stars? And that the first day was, as it were, also without a sky? And who is so foolish as to suppose that God, after the manner of a husbandman, planted a paradise in Eden, towards the east, and placed in it a tree of life, visible and palpable, so that one tasting of the fruit by the bodily teeth obtained life? And again, that one was a partaker of good and evil by masticating what was taken from the tree? And if God is said to walk in the paradise in the evening, and Adam to hide himself under a tree, I do not suppose that anyone doubts that these things figuratively indicate certain mysteries, the history having taken place in appearance, and not literally.

And Augustine of Hippo, the famous bishop of the early church, also expressed openness to an evolving world, a single moment of creation, and a non-literal reading of the Bible. His concern was that Christians, by using the Bible in ways that contradict human reason, would make themselves ridiculousand damage the power of their witness:

Usually, even a non-Christian knows something about the Earth, the heavens, and the other elements of this world, about the motion and orbit of the stars and even their size and relative positions, about the predictable eclipses of the sun and moon, the cycles of the years and the seasons, about the kinds of animals, shrubs, stones, and so forth, and this knowledge he holds to as being certain from reason and experience.

Now, it is a disgraceful and dangerous thing for an infidel to hear a Christian, presumably giving the meaning of Holy Scripture, talking nonsense on these topics...

Allegorical interpretations have a long history among Christians, though a historically recent push for the idea of Biblical inerrancy and literal readings has led many American evangelicals to embrace creationism. (Pew's 2013 survey found that among white evangelical Protestants in the US, 64 percent believed that "humans existed in present form since beginning"—the highest of any religious group.)

But even among evangelicals, people like televangelist Pat Robertson—yes, Pat Robertson—fear Ham is making Christians look bad.

"We have skeletons of dinosaurs that go back 65 million years,” Robertson said this week on his TV show, The 700 Club. "To say it all dates back to 6,000 years is just nonsense... Let's be real; let's not make a joke of ourselves."

A new Noah

Inside a glass case near the end of the Creation Museum's exhibits rests a picture of Ham's parents, along with a miniature Noah's Ark. Ham's father Mervyn built the model in the 1990s and hoped to present it to his son when Ham visited Australia in 1995. Instead, though, "Ken's dad passed into the presence of his Creator and Lord two weeks before Ken's visit." Next to the model is Mervyn Ham's Bible, opened to the first page of Genesis, a mass of notes and underlines.

For Ham, his life's work is also his family legacy. "Winning" or "losing" a debate with Nye doesn't matter; spreading the message does.

Enlarge / The Ark Construction Site at the Creation Museum.

Next up for Ham's message is a 500 foot long reproduction of Noah's Ark, to be built just off I-75, 45 minutes south of the Creation Museum at a cost of $25 million dollars (only $14 million has been raised so far; Slate recently charged that the project is being funded by junk bonds). Many millions are needed to flesh out the project's future phases, which include a replica Tower of Babel, a walled city, and a first-century village.

Ever grandiose, Ham says that his Ark Encounter will "become an attraction that will capture the world's attention." A flyer encouraging people to sponsor Ark pegs for $100 a pop or planks for $1,000 also notes that the Ark could be "one of the greatest evangelistic outreaches of our time."

But while this modern-day Noah waits to build his Ark, he still has the Creation Museum and a newly public platform to promote its ideas. The debate with Nye "has drawn countless believers and unbelievers alike to consider the Creation Museum’s teachings about the true history of the universe,"wrote an AIG staffer after the debate.

For mainstream scientists, it's a terrifying thought.

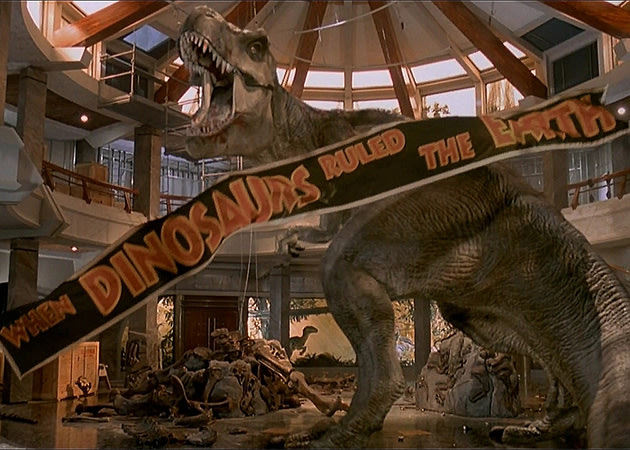

Universal Pictures

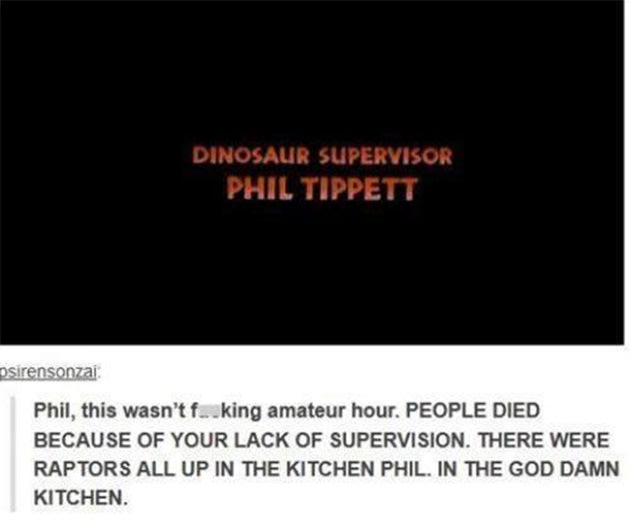

Universal Pictures Universal Pictures

Universal Pictures Jurassic Park

Jurassic Park Universal Pictures

Universal Pictures via Tumblr

via Tumblr